The last two parts of this series were probably daunting. Makes sense; all this stuff is hard! I mean, I enjoy doing all the planning part, but I have a tendency to over-complicate everything, which naturally makes it easier for it to break down, fall apart, explode in my face.

So how do we set goals, and how do we achieve them, or at least make decent progress on them?

That’s what I’m going to talk about today.

It’s all about simplicity and making things habits.

“But J!” I hear you say, “I have ADHD! I can’t be consistent enough to make something a habit! I chafe at the rigidity of routines! I need variety in my life!”

What if I told you that it’s possible for ADHDers to:

- Create new habits and

- Enjoy following routines, all while

- Incorporating the novelty and variety that our brains crave?

Sounds too good to be true, doesn’t it? Well, it kind of is. Because doing all of this, getting a system in place and maintaining it, isn’t easy. It’s hard work. But it’s worth the effort.

Over the last couple of years, I’ve read both Tiny Habits (BJ Fogg) and Atomic Habits (James Clear). Neither book contained new information, but both provided a reframe on how we form habits and why stuff is hard.

First things first, let’s talk about behaviour. There’s a whole branch of psychology that studies behaviour and how people (and animals) learn to do or not do things. Behaviourism as a discipline isn’t awful, but some of the ways this knowledge is applied certainly are. Happily, what we’re going to discuss here is pretty neutral.

The basics of behaviour are pretty simple.

- Antecedent—The “trigger” for the behaviour.

- Behaviour—What you do in response to the antecedent.

- Consequence—What happens as a result of the behaviour.

When you’re trying to figure out how to change a behaviour, it helps a lot if you can figure out what’s going on when you do it and how you feel during or afterwards. That’s where your “why” is hiding.

The other part that’s most important to understand is how the interplay of motivation and ability affect your ability to change your behaviour. Here’s a really simple graph to illustrate.

Motivation is on the left, and ability is across the bottom. The curvy diagonal line is the “sweet spot” where the behaviour is most likely to occur. You’ll notice that when motivation is low, then it needs to be easy to do or it won’t happen. If you’re really motivated to do it, then it’s okay if it’s more difficult.

We’ll, that’s how it works for neurotypical people, at least. Executive dysfunction means our graph is way messier and not so straightforward. But! If we make things as easy as possible, then often we can sidestep our executive dysfunction and actually get stuff done.

In Tiny Habits, BJ Fogg gives a really simple “recipe” for building a habit.

“After I [Antecedent] I will [Smallest first step possible] and I will celebrate by [something that makes you feel great when you do it].”

Tiny Habits, BJ Fogg

There are two things that are really important with the Tiny Habits method. First is the Antecedent, or trigger. Another way to think of this is as a prompt. That’s why the recipe begins with “after…”: the new behaviour is something you’re going to do after something you already do all the time. It’s important to note that if you have low motivation to do something and it is really difficult, then that prompt isn’t going to work.

The other important part of this method is to celebrate immediately after you complete the new behaviour. This ties the excited feeling and burst of dopamine to doing that thing, which will help you remember to do it again next time. Remember, the ADHD brain has trouble with dopamine; most of us either don’t have enough or we don’t use it effectively. That means we are always looking for more. So anything that gives us that surge is something we’re going to want to do more often.

James Clear talks a bit about this (he’s done some studying under Dr Fogg), but his book takes things further and smaller (hence “atomic”—he’s going smaller than tiny). I’ve incorporated both books into my current approach to life and seen some success. So I’m going to explain it now.

The first thing is to figure out what you already do. It doesn’t have to be precise, just make a list of what you do every day, in order. You can do this for several days in a row and then see where things repeat—for example, I get up every morning and use the bathroom, then I make the bed and get dressed, and then I do my hair.

Now that you know what you do, it’s time to decide what you’re going to add.

Just like last week, we begin by dividing our lives into 5 or 6 different categories. This is important because we don’t want to take on too much. The point here is to make stuff easier, not to make it all as complicated as possible!

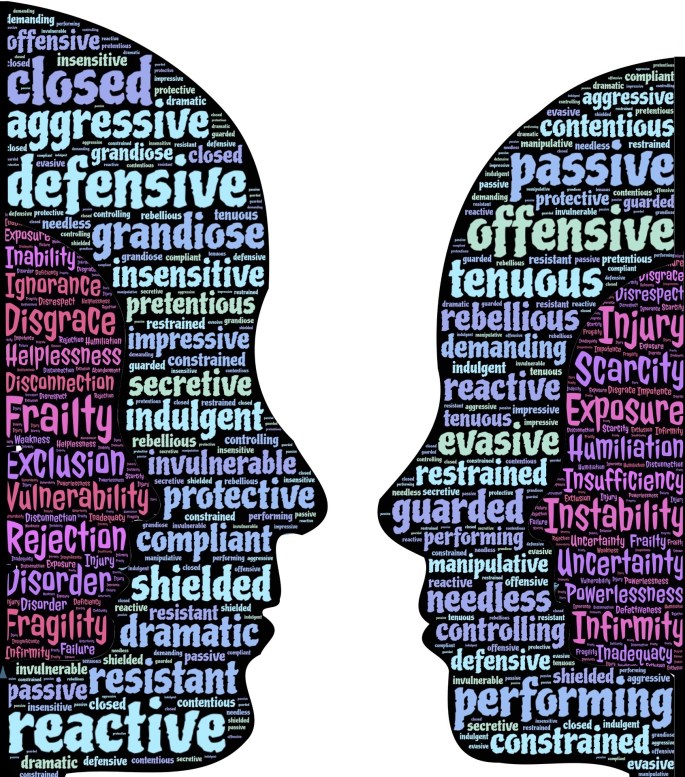

Now you get to daydream a little. Think about the things you value about each life category, and think about people you know or characters from TV, movies, or books (etc.) who exhibit those values and qualities. The idea is to think about what kinds of things those people do that reflect their values, because that’s going to get you to the next step.

Write down the things those people do and the values and qualities they exhibit. Then write yourself a positive statement that attributes all of these things to you. Start this sentence with “I am the kind of person who…”

You’re probably feeling a bit weird about writing something like “I am the kind of person who puts things away and does the dishes every day” if your house is a perpetual disaster. The thing is, this isn’t lying, it’s stating your values in a positive way, to remind you what’s important to you and why you’re doing the things you’re doing. It’s an aspirational message: you aren’t there yet, but you’re working on it and you’re doing your best.

Once you have a statement for each life category, you get to pick one thing in each that you’re going to start doing. Except you’re going to make that one thing the absolute smallest thing you can possibly think of.

Let’s say that you have a life category for physical health, and your statement is “I am the kind of person who eats well and exercises regularly.”

Thinking about people who eat well, you decide that you want to start eating more vegetables. But that’s pretty vague, and vegetables can be time-consuming to prepare, and they can be expensive.

So you decide to have fresh vegetables for an afternoon snack every day, and that you will get bags of baby carrots or snap peas, or a prepared veggie tray for this purpose every week when you get groceries.

You decide to keep these snacks on the top shelf of the fridge so you see them when you go looking for something to eat.

Your “recipe” reads as follows: “After I feel hungry in the afternoon, I will eat one fresh vegetable as a snack, and I will celebrate by clapping my hands.”

Most things you’re going to consider doing will require a bit of prep work, as with the example of eating more vegetables. The key is to keep the prep simple (e.g., by buying vegetables that are ready to eat and don’t need to be cut up or anything) and set yourself up for success by making whatever you need easily accessible (e.g., by putting the vegetables in a visible location in the fridge). Oh, and you definitely need to choose vegetables that you like and will want to eat!

So I think we’ve covered all of the important bits here. We’ve tied eating vegetables to afternoon hunger and made it easy to remember to eat the vegetables and to actually eat them. We want to be healthy, and we like the vegetables we’ve chosen. We’re celebrating as soon as we’ve eaten the vegetables. All of these things will help us turn eating vegetables into a habit.

What about consistency?

Well, James Clear likes to track his habits and he does regular data reviews and stuff. If you like tracking stuff and like data, go ahead. But it’s not necessary. In fact, BJ Fogg says that the common factoid of “it takes 28 days to form a habit” isn’t really true. And if you miss your habit one day, just do your best to do it again the next day.

That’s it. That’s how you do it. Be as consistent as you can, but don’t worry too much about a missed day here and there.

Obviously breaking things down can be hard. Same with figuring out how to set yourself up for success. But that is part of what Actually ADHD (and its sibling Tumblr, “How Do Thing?“) is for. So if you need help with any of that, don’t be afraid of the ask boxes!

Next week we’ll finish up this month of goal-setting by talking about a strategy I find helpful on Bad Brain Days, and we’ll talk about that all-important “immediacy factor.”